Tudor Society Introduction

Tudor society took the form of a hierarchical system with the King at the top. Those at the top were rich and powerful while those at the bottom were poor and had no power at all. People were taught by the church that their position in life was determined by God; if you were born poor there was little chance of you becoming rich. Most people accepted their position in life without question.

Thomas Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell are examples of men who were born poor and rose to the very top of society through the church; but they are exceptions to the norm. While it was very rare for the poor to rise in society, it was possible for the rich and those in power to lose everything, including their head. Displeasing the monarch, a failed investment or a succession of poor harvests are examples of how the wealthy could become impoverished.

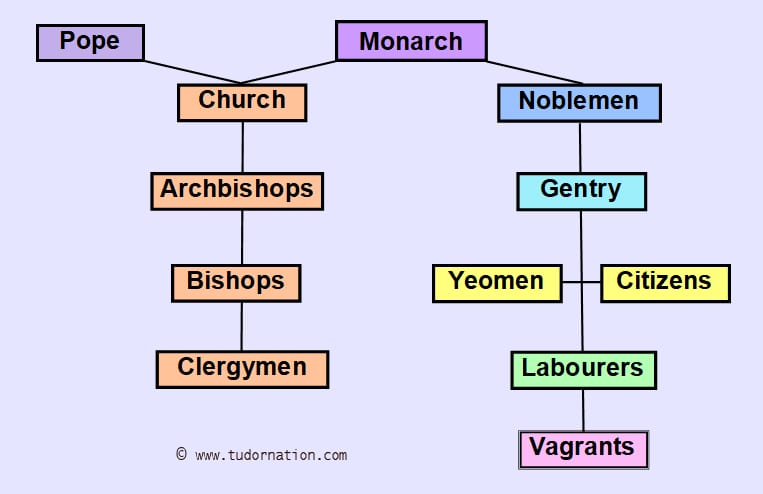

Tudor Society can be divided into seven different categories:

1. The Monarch

The monarch was the head of Tudor Society, answerable only to God (and the Pope before the Reformation). He or she was the richest person in the country, owning vast amounts of land and numerous properties. All people were bound to serve their monarch and failure to do so was considered a treasonable offence punishable by death.

The King or Queen made all the laws of the land but took advice from members of the Privy Council. The Wars of the Roses had shown that a monarch was not secure without the backing of his noblemen and the monarch rewarded his trusted nobles with titles and positions.

There was a justice system in Tudor England but few judges would dare to pass judgement against the King’s wishes. The trial of Anne Boleyn is a good example of the power of the monarch in the judiciary, not one would have defied the wishes of King Henry VIII.

2. The Church

The church was very powerful and owned a lot of land. All people were expected to attend church on Sundays and religious holidays. During the reigns of Henry VII, Henry VIII and Mary I church services were delivered in Latin. Few people understood Latin and the use of the language added to the wonder and awe people felt towards religion. Edward VI was a committed Protestant and during his reign services were delivered in English and a new Prayer Book was introduced. Elizabeth I also sanctioned church services in English but she also allowed Latin prayer books.

After the break with Rome, Henry VIII authorised the dissolution of the monasteries. Monastic land was confiscated and became the property of the Crown.

The church hierarchy of archbishops, bishops and clergymen was retained after the English Reformation. The church was the one area of Tudor society where it was possible to rise through the ranks and there was a huge difference in the wealth, power and lifestyle of an archbishop and a clergyman.

Archbishops

The position of archbishop was the highest rank in the church. They were rich and powerful with the Archbishops of Canterbury and York being the most important. Archbishops played a role in the government of the country and had a great influence on the monarch. After the break with Rome they were appointed by the monarch rather than the Pope and their position was dependant on their remaining in favour. Thomas Cranmer rose to become Archbishop of Canterbury after helping Henry VIII to secure his divorce from Catherine of Aragon by breaking with Rome. When Mary I became Queen Cranmer was charged with treason and executed.

Bishops

Bishops ranked below archbishops, but bishops of the largest dioceses were wealthy and held power. After the Reformation they were liable to lose their position and even their life if they did not support the monarch. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, did not support Henry VIII’s divorce of Catherine of Aragon nor the break with Rome. He was found guilty of treason and executed in 1535.

Clergymen

Clergymen were the lowest rank in the church. They lived in towns and villages and delivered local church services. They also visited the sick and tried to help the disadvantaged in society. Clergymen also taught local children from those families that could afford to pay. They did not earn very much and most led simple lives, but they were respected members of their local community.

3. Noblemen

Noblemen were born rich and came from families with hereditary titles – Barons, Earls and Dukes. There were around 40 noble families during the Tudor period. Most owned large country estates and were often close friends to the monarch.

Noblemen were appointed to top positions such as the Privy Council which advised the monarch. Military leaders were also members of the nobility.

Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, uncle of both Anne Boleyn and Kathryn Howard, rose to a very high position during the reign of King Henry VIII. He served as a military commander during the wars with France and also as a Privy Councillor. He promoted both his nieces and worked to bring about the fall of both Thomas Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell. Howard presided over the trials of his niece Anne Boleyn and her brother George and delivered the guilty verdicts. When Kathryn Howard was arrested he denounced his family and supported their imprisonment.

He fell from favour after lifting the siege of Montreuil, against the King’s wishes, in 1544 during the war with France. He was found guilty of treason and sentenced to be executed in 1547 but escaped execution when the king died the day before his sentence was to be carried out.

4. Gentry

Members of the gentry were wealthy landowners who lived in the country. There were around five thousand members of the gentry. Of these about 500 had been knighted by the monarch. Members of the gentry fought for the monarch in times of war. They also served as local sheriffs or justices of the peace and helped to govern at a local level.

It was possible for members of the gentry to rise and become noblemen. John Seymour, father of Jane Seymour, was a member of the gentry who had been knighted in 1497. His family home was Wulfhall in Wiltshire. King Henry VIII visited the Seymour family in 1535 during his summer progress.

Henry VIII married Seymour’s daughter, Jane in 1536. After the birth of Prince Edward in 1537, Seymour’s son Edward was created Earl of Hertford. After the death of Henry VIII he took the position of Protector of England and the title Duke of Somerset.

5. Yeomen and Citizens

Yeomen and citizens were fairly wealthy men. They were farmers, merchants and artisans that had made enough money to own their own houses and employ servants. Some were as wealthy as members of the gentry but they did were not landowners so could not rise to that position of Tudor society.

Yeomen lived in the country and farmed the land. Some yeomen owned land while others rented it from gentlemen. They were generally rich enough to be able to afford labourers to do the heavy farming jobs for them.

Citizens lived in the towns and were merchants or artisans. Merchants made money by trading goods with ship owners. Artisans were skilled craftsmen who could command a good price for the goods that they made. They often belonged to guilds representing different trades.

In 1588 the Guildhall in York was given the title: Company of Merchant Adventurers of York by Queen Elizabeth I.

6. Labourers

General labourers were employed by yeomen or citizens and were paid a wage for their work. They were generally given the more labour intensive and heavy jobs on farms or in artisans studios. Skilled labourers had received some training and could help with more specialised tasks.

In 1515, an act of Parliament fixed the wage of a general labourer at 3d per day in the winter months and 4d per day in the summer. Farm labourers were often paid a bonus once the harvest was in. They were expected to work six days a week – Monday to Saturday – from sunrise to sunset in the winter and from sunrise to early evening in the summer. Skilled labourers were paid 5d per day during the winter and 6d per day during the summer months.

7. Vagrants/Beggars

These formed the lowest and poorest section of Tudor society. They included those who were old, sick, disabled or unable to work. Because they did not work and they earned no money and were forced to beg on the streets for money or food. Before the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536 this section of society would have been helped by the monks and nuns of the monasteries and abbeys.

The Tudor period saw a growing number of vagrants who preferred to beg on the streets rather than work. To try to alleviate this problem a Poor Law was introduced in 1563. The law distinguished between those who could work but chose not to (undeserving poor), and those who wanted to work but could not find employment (deserving poor). The undeserving poor would be punished while the deserving poor would be helped.

In 1572 a new local tax, called the Poor Rate, was introduced. Wealthy landowners were taxed and the money used by town councils to help the poor.

The 1601 Poor Law added provision for orphaned children to be apprenticed and established poor houses for the homeless.

Published Jun 2020 – Updated – Nov 23 2024

Harvard Reference for this page:

Heather Y Wheeler. (2020 – 2025). Tudor Society Available: https://www.tudornation.com/tudor-society Last accessed April 14th, 2025