Who was Richard Hunne?

Richard Hunne was an English merchant and tailor who lived in the parish of Whitechapel in London. In March 1511, his five week old baby son, Stephen, died. Hunne took his son’s body to St Mary’s Church in Whitechapel to be buried by the parish priest, Thomas Dryffed.

It was customary for the priest to receive, as mortuary fee, a piece of the deceased’s property. As a five-week old baby had no property, the priest demanded the child’s winding sheet (a piece of cloth that a body was wrapped in). Some sources state that the priest requested the child’s bearing sheet (the cloth he was wrapped in for his christening).

Hunne was angry and resentful that the church had the power to demand such a payment with no regard for its sentimental value to Hunne and his wife. He decided to challenge the Church on this matter. He argued that in common law a corpse cannot own property and that as the winding / bearing sheet did not belong to the dead child the priest had no claim to it.

Court Cases

In the Spring of 1513, Thomas Dryffed took Richard Hunne before the Archbishop’s court for non-payment of the mortuary fee. Hunne maintained that as it was he who was being asked to pay the mortuary fee the child’s winding / bearing sheet could not be demanded. The case was heard by Cuthbert Tunstall, Chancellor to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who found in Dryffed’s favour and ordered Hunne to pay what he had been asked.

In December 1512, Hunne attended evensong at St Mary’s Church. Dryffed’s Chaplain, who was taking the service, refused to begin until Hunne left the building. Richard Hunne claimed that the Chaplain shouted “Hunne, thou art accursed and standest accursed!” This implied that Hunne had been excommunicated by the church.

In the Spring of 1513, Richard Hunne brought two cases before the King’s Bench. Thomas Dryffeld’s Chaplain was sued for slander with the claim that his implication of excommunication had harmed Hunne’s reputation and damaged his business.

A writ of praemunire (acting outside the sovereign’s mandate) was brought by Hunne against Thomas Dryffeld on the grounds that by prosecuting him in an ecclesiastical courts made him guilty of praemunire because he had exercised a power which was derived from a foreign sovereign, namely the Pope.

Bishop Fitzjames’s Response

Richard Fitzjames, Bishop of London was worried about the future of the church if Richard Hunne won his case against the Church. Reformers like John Colet and John Wycliffe were winning great support and were bringing the Catholic church was in disrepute. If Hunne were to win his case this would greatly benefit the reformers.

Fitzjames ordered his men to arrest Hunne on suspicion of Lollardy (a term given to followers of John Wycliffe that favoured church reform) and to search his house for any heretical material. Hunne was duly taken to Lollard’s Tower, a prison in St Paul’s Cathedral.

In early December 1514, Richard Hunne was interrogated by Bishop Fitzjames and his chancellor Dr William Horsey. He was questioned about the criticisms he had made of the church, and also about the Lollard writings and the Wycliffe Bible that had been found in Hunne’s house.

Richard Hunne’s Death and Inquest

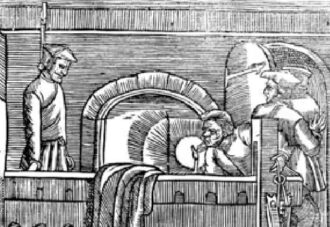

On 4th December 1514 Richard Hunne was found hanging from a beam in his cell. Although his jailors insisted that guilt had driven him to suicide his friends maintained that he had been murdered.

The following day a coroner’s court was convened to discuss Hunne’s death. The coroner was Thomas Barnewell and the jury made up of 24 leading landowners.

The court heard that Hunne had bled when he died but that his blood-stained jacket was found neatly folded some distance away. Hunne’s neck had been broken and there were marks around his wrists which suggested they had been bound but when he had been found his arms had been hanging loose. The inquest concluded that Hunne had been murdered by his jailors Charles Joseph, John Spalding and Dr William Horsey, chancellor to Richard Fitzjames.

On 16th December, William Fitzjames held a trial of heresy against Hunne. He was posthumously tried in the chapel of Our Lady at St Paul’s. He was found guilty, excommunicated and his body was burned as a heretic.

This action by Fitzjames caused widespread anger among the people of London. Richard Hunne’s friends claimed that Fitzjames and Horsey were guilty of praemunire for burning Hunne’s corpse.

The Criminous Clerks Act

On 5th February 1515, Convocation met to discuss the Hunne case. The opening speech was made by the Abbot of Winchcombe, Richard Kidderminster, who disputed Parliament’s ability to pass legislation relating to the clergy and claimed that the privileges of the clergy had been infringed when Horsey had been prosecuted by the King’s Bench for the murder of Richard Hunne.

Kidderminster also attacked the 1512 Criminous Clerks Act which prevented clerics in minor orders from claiming benefit of clergy. He argued that clerics in minor orders were just as holy as those in major orders and that as those in major orders were not covered by the act then neither should those in minor orders be.

He concluded that no priest or holy man should be tried in the secular courts and that the procedures in the 1512 act were wrong.

Following the conclusion of convocation, Bishop Fitzjames wrote to Wolsey on behalf of Dr Horsey who was to be tried for the murder of Richard Hunne. He asked Thomas Wolsey to explain to the King that as Horsey was technically a clerk he should be allowed clerical privileges and therefore could not be tried in a secular court.

In mid February the House of Commons attempted to modify the Criminous Clerks Act to cover all clerks. It was thrown out by the House of Lords, the majority of whom were Bishops and Abbots.

The House of Commons, alarmed by the action of the House of Lords and Kidderminster’s speech to convocation, appealed for the King to intervene. Henry agreed and called for a conference to be held at Blackfriars later in the year.

Blackfriars Conferences

In November 1515 a conference was held at Blackfriars to decide whether Richard Kidderminster had been justified in using Convocation to speak against the 1512 Criminous Clerks Act. Henry VIII’s chaplain, Dr Henry Standish, a member of the Franciscan order and Warden of Greyfriars in London, spoke in favour of the Act saying that it was in the public’s interest that murderers be punished and because the good of the public was the Crown’s responsibility then the Crown had the right to punish any who were guilty of breaking the law. He went on to say that in England papal decrees were not upheld if they were unacceptable to the Crown or contrary to local customs.

The Church responded by saying that immunity from secular laws was theirs by divine right and passages from the Bible were used to support their claim. ‘Touch not the Lord’s anointed’ was taken to mean that as the clergy were anointed by the Lord they could not be touched by the secular system. ‘Honour thy Father’ meant that as a child has no jurisdiction over his earthly father neither should a lay man have jurisdiction over his heavenly father, holy father or priest.

In November 1515, Dr Henry Standish who had spoken in favour of the Criminous Clerks Act, was summoned before Convocation. He was closely questioned regarding his beliefs and opinions. Standish immediately appealed to King Henry for support. Henry duly ordered a second conference to be held.

In the second Blackfriars conference, Dr Henry Standish was supported by John Veysey, doctor of civil law and Dean of the Chapel Royal. After hearing both sides the judges declared that those members of the clergy who had questioned Standish in November were guilty of praemunire.

Baynards Castle Assembly

King Henry VIII presided over an assembly of both Lords and Commons at Baynards Castle in November 1515. Thomas Wolsey, as leading representative for the clergy, knelt before Henry and stated that in no way had Convocation intended to invade his prerogative and asked that the case be sent to Rome for clarification.

Henry refused and declared ‘by the ordinance and sufferance of God we are King of England and the Kings of England in times past have never had any superior but God alone. Know you well that we shall maintain the right of our Crown and of our temporal jurisdiction as well in this point as in all others.’

Despite Henry’s statement, the amendment to the Criminous Clerks act was never put into law.

Trial of Horsey, Joseph and Spalding

in late November 1515, Dr Horsey, Charles Joseph and John Spalding were tried for the murder of Richard Hunne. Their pleas of not guilty were accepted, although the indictment for murder was upheld. They were quietly removed from London and found alternative employment elsewhere.

Convocation consequently dropped all charges against Henry Standish.

Fearing reprisal from the House of Commons and that the case would drag on, Wolsey advised Henry to dissolve Parliament which he duly did.

Why is the Richard Hunne Affair Important?

The controversy surrounding Hunne’s death escalated into what is known as the ‘Hunne Affair’. It is a significant event in the history of the English Reformation as it fuelled anti-clerical sentiments and raised questions about the church’s practices and its influence over the legal system. It also highlights the separation of Church and Parliament and the difficulties where one tries to have influence over the other.

The Hunne Affair contributed to the growing dissent against the Catholic Church in England and played a part in setting the stage for the later reforms and ultimately the English Reformation of the 1530s. It also served as evidence of the power of the Catholic Church over that of the King, a fact that encouraged Henry to declare himself Head of the Church in England in the 1534 Act of Supremacy.

Published Mar 29 2024 @ 7:16 pm – Updated – Dec 09 2024

Harvard Reference for this page:

Heather Y Wheeler. (2022 – 2025). The Richard Hunne Affair a detailed account & analysis Available: https://www.tudornation.com/the-richard-hunne-affair Last accessed April 16th, 2025